If you go through the latest Bollywood filmography and TV shows, it will stand out that the industry is choosing to tell stories around the prevailing social stigmas. It is perhaps a way for the industry to go back on its outdated moral preachings and help generate new subversions. Some of these instances are mellow and have garnered a nod from most critics. For instance, Deepika Padukone’s character, Rubina Mohsin, in Pathaan (2023), plays its part in reclaiming the stereotypical female character in a testosterone-rich espionage movie. She has her own narrative, motivation and skillset to participate in action beside Pathaan (played by Shah Rukh Khan); she is NOT a damsel-in-distress.

In most other cases, Bollywood’s messaging has gotten bigger and, dare I say, better with time. While Akshay Kumar’s Toilet: Ek Prem Katha (2017) may have kickstarted this phenomenon, the messaging seems to have caught up with most of the pandemic and post-pandemic releases. From Bulbull (2020) and Pagglait (2021) to Darlings (2022), Badhaai Do (2022), Jayeshbhai Jordaar (2022), Satyaprem ki Katha (2023) and even a KJo movie, Rocky Aur Rani ki Prem Kahani (2023), Bollywood movies have managed to talk about sanitation, female foeticide, and several forms of sexual violence, informing the audience about the various spectrums of the LGBTQIA+ community, and drawing light upon the experiences of those who face caste, class and gendered marginalization in society.

However, with the latest Made in Heaven Season 2, most people seem to be expressing an inevitable tiredness towards the bold-letter messaging that has become a prevalent norm in pop culture releases. MIH S02 tries to condense almost all aspects of societal injustice into seven lengthy episodes, including the obsession with fairness, violation of consent among teenagers, domestic violence, polygamy, experiences of transwomen, systemic abuse towards queer people in their families, etc. Apart from the fact that most of these movies and OTT releases appear to be hellbent on mansplaining or ordaining upper-class, upper-caste, heterosexual men as the spokesperson of the causes held up on the screen, I cannot help but cheer for the big, bold Bollywood movie and/or TV show messaging in pop culture.

Satyaprem Ki Katha (2023) is a case in point. Although it is Katrik Aryan’s character, Sattu, whose insistence on telling the truth and fighting for justice towards his wife drives forward the film’s plot, it is impossible not to notice that Kiara Advani’s character, Katha, gains more and more confidence as the big secret about her previous experience of assault is brought out in front of her in-laws and, later, the public. Victims of sexual assault may require some support in their drive for justice, so Sattu’s expression of his love for Katha through his unwavering support in her fight is just the way I would have wanted Bollywood cinema to understand and expand its horizon of looking at and understanding one’s love towards one’s partner.

Even in Jayeshbhai Jordaar (2022), Ranveer Singh’s character, Jayeshbhai, is not only faithful in his respect towards his heavily-pregnant wife but also the one to stand up against his traditional family and its rigid belief systems. These characters are tending to be green flags, as Gen Z would call them, even though the movies they feature in are yet to fathom the idea that women can, in fact, fight their own battles. The messaging in both these movies is over the top. Still, it drives home the idea that it set out to preach – perpetrators of sexual violence must be punished, and female foeticide is a crime no less than homicide, respectively – by the time the credits start rolling in the end.

It may also be essential to note here that all Bollywood movies or TV shows are not targeted toward the same audience. The above-mentioned movies are situated in the heart of western India and primarily seek to deliver their message to the middle-aged, middle-class population; they are Hindi movies made for families to watch on their television screen post lunch on a Sunday. Similarly, Rocky Aur Rani ki Prem Kahani (2023) is parcelled as a family blockbuster and addresses all generations. Ranveer Singh’s Rocky is again a lesson in green-flag boyfriend behavior for people in their 20s, while the Dharmendra-Shabana Azmi romance sub-plot is meant to tickle the nostalgia of the 80s generation and simultaneously drive home a point about the plausibility of sexual attraction and romance between the aged.

I would rather appreciate this period of Bollywood stepping out of its comfort zone and holding up placards full of social messages for its audience than going back to watching Suraj Barjatiya’s honey-sweet family dramas blinded by middle-class mentality and moralities. Even for MIH S02, the truths around social injustices may be prickly for those tired of seeing one after another social cause being highlighted on screen, acknowledging fully well that microaggressions around these causes exist. I say, why not step out of the liberal’s shoes and look at how this show, along with most OTT releases, maybe voicing the everyday struggles of those who are faced with several kinds of marginalization in society?

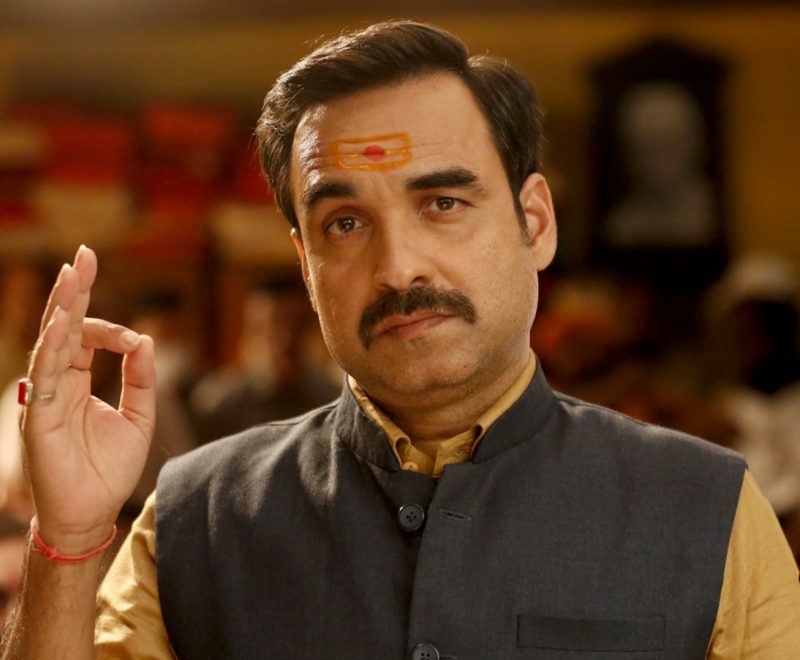

Lastly, although Hindi cinema and OTT releases continue to struggle with representation, especially as the shoes of characters from the queer and Dalit communities continue to be filled in by heterosexual and upper-caste actors, the current releases are thankfully not shying away from the representation on these marginalized communities on the big screen. Senior Inspector Anjali Bhaati (played by Sonakshi Sinha) in Dahaad (2023), a crime-thriller OTT show by Amazon Prime India, represents a Dalit policewoman and the politics of power around her that is affected by her caste and gender identities. Similarly, Dr. Trinetra Haldar Gummaraju’s role as a transwoman in MIH S02 may be the first (here’s hoping that it won’t be the last) time that a trans character’s life and identity are adequately accommodated in a TV show narrative.

I am glad that through these characters, Bollywood films and TV shows are atleast trying their best to visibilize the communities that have for years now suffered due to misappropriation and stereotyping at the hands of the upper-class, upper-caste, heterosexual male-centric writing.

In holding up the struggles of the marginalized communities and incessantly about the existing social injustices, these shows and films are doing their part in coming out to support the ongoing fight against hetero-patriarchal horrors in society. In short, a part of Indian pop culture – Bollywood movies and TV shows – is actively stepping up to the politics of queerness, caste representation and necessary socio-cultural subversions.

It has found directors like Karan Johar, who sought to draw humor out of homophobic side-characters in Kal Ho Na Ho (2003) and Dostana (2008), introduce a sub-polt highlighting the struggles of his female protagonist’s father (because he wanted to become a Kathak dancer) in his latest release. The latter is reclaimed when Rocky and he perform a Kathak dance to a famous Sanjay Leela Bansali song during Durga Puja celebrations. If this translates to loud and bold-lettered messaging, so be it; atleast we have set out in the right direction. One can only hope that as time passes by, Bollywood will do its part in contributing to these caste, class and gender politics with finer nuance and more diverse representation.