For most of my childhood, I was an adamant lover of contemporary Bollywood films. But for some reason, I largely overlooked the films that came out during the early 2000s that had come out before my formal introduction to cinema. While much of this stemmed from the fear of missing out on the newer releases, perhaps I was the kind of kid who wanted to dive more into the kind of cinema that particularly reflected the sensibilities of my generation.

This, however, changed when I got introduced to American and British films in my late teens. The excuse of overlooking these films now seemed to be secondary to my tendency of brushing them off for being inferior in quality. The kind of cinema I was watching in my highschool opened my imagination to the varied forms of ingenious storytelling cinema was capable of. Although that phase of my life opened me up to the kind of experience that would shape my knowledge of film grammar, it left me with a watered down and indiscrete perception of Bollywood. I became hyper-sensitized to the politically correct messaging preached by some of the foreign films to claim anything else as irresponsible and slipshod.

Earlier this year, when I took up the task of reviewing KJo’s latest film, Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani, I dared to plunge myself into exploring the director’s late 1990s-early-2000s work. Not surprisingly, I almost got ostracized out of my social circle when I revealed to people how it would be my first time watching films such as Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna and Kuch Kuch Hota Hai. While I had some reservations about these films, I couldn’t help but get lured into their seamless compositions. And no, I don’t just mean the musical numbers, but the way in which the films breathed an unabashedly committed vigor into their core thematics. By the time I had stumbled upon Nikkhil Advani’s directorial debut (which was written by KJo), the fear of missing out on an era of Bollywood that I had foolishly been passive to all my life began to consume my formerly naive perception of it.

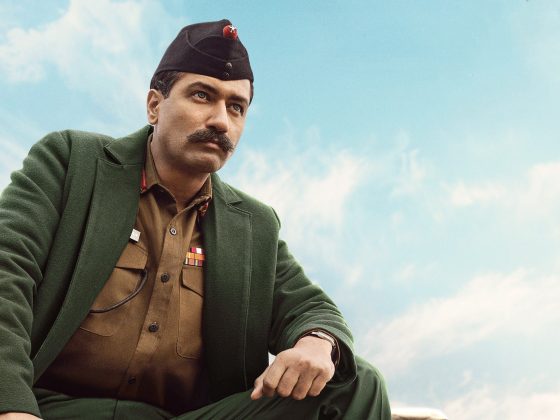

By the time Kal Ho Naa Ho had come out in 2003, mainstream Bollywood no longer remained national cinema, but a transnational one – not only in terms of production but in terms of the audience as well. A decade had passed since our country had embraced liberalization, and perhaps the most important reason for the global proliferation of Bollywood was in how South Asians, especially middle to upper class, high-skilled workers, were now starting to immigrate to the West. The ‘Indian’ identity as represented in the newer Bollywood films now increasingly became transnational in outlook. The NRIs were not villains anymore who needed to be saved from Western corruption, but Indian aristocrats based in first-world nations.

And then came a screenplay that borrowed the terminally-ill savior angle from the Hrishikesh Mukherjee classic (not without losing the Homoeroticism touch), but this time by basing it this time in a distant NRI setting. In Advani’s feature debut, characters talked the way normal people do, not shackled by the contemporary notions about towing the line between political correctness on either side that now finds most Bollywood writers in a paranoid dilemma. Perhaps that what remains the biggest testament to the long lasting cultural influence exhibited by the film. The kind which transcended the problematic aspects of the savior trope formula by imbuing its lead male with an unbridled emotional maturity while informing the emotional dynamics that surround him through its strong female lead.

By establishing the framing device through Preity Zinta’s Naina Catherine Kapur’s perspective, the film adroitly deflected itself from the conventional tropes of Bollywood with a voice of agency. It’s through this that the movie painted an angsty embodiment of the aspiring youth, so burdened by the troubles of life that they forget to see how life in itself is a gift. It’s through her that we appreciate the new world that SRK’s Aman paints for us. A man so full of unbridled joy that his heart literally grows old by the weight of his love for others, Aman plays the most selfless and charming guy you’d probably ever see in a film. It even leads an uptight Naina to eventually fall hopelessly in love with him. But this also makes way for one of the most earnestly written male characters in Bollywood.

It’s through Saif Ali Khan’s Rohit that “Kal Ho Naa Ho” displays an unforgettable image of unrequited love. The recurring motif of the color red consistently acts like the kind of unresolved conflict that becomes too fragile to even address. When I watched the scene where Rohit, wearing a muted pink tie, and Naina, wearing a baby pink dress, discuss the latter’s fading love, it made me wonder how Bollywood has simply forgotten to capture such an instinctive feeling. He very much invokes KJo’s own ‘pyaar dosti hai’ idea from the 1998 film, but without resorting to cliched notions of a rejected lover. While Aman’s angelic figure becomes a means of uniting a broken family through eternal love, Rohit’s mantra of using his one sided love to reproduce more love solidified the film’s unprecedented potential in shaping an entire generation’s idea of love.

I could go on and on about how KKHH came across as one of the best shot Bollywood films of the past couple decades, or of how instinctive Shankar-Ehsaan-Loy’s groundbreaking work remains so many years later. Or I could sound all intellectual and go on about the film’s important place in culture in navigating the issue around community building, as it coincided with the aftermath of 9/11 and the racism that disaster had brought. Above all, there’s the solid case it makes for how even the notions of globalization wouldn’t negate the beating desire for Indians to watch melodrama that’s executed like an action set piece.

But the most enlightening takeaway watching “Kal Ho Naa Ho” for the first time 20 years after its release remained in the realization of just how masterfully a story could be told despite its many tonal shifts. I wouldn’t change a thing about the way in which International cinema had conditioned me in my late teens, but watching this film for the first time around its anniversary made me realize just how important it is to remind yourself of love through the unbridled power of cinema. After sensitizing myself with various styles of filmmaking, I circled back to the immoderate kind Bollywood has always embraced. And Kal Ho Naa Ho’s charm remains a testament to how well it embodied that. All these years later, I happened to fall in love with this movie despite some of its dated elements, because I know how making politically correct movies is easier. It’s much more difficult to make one with a heart that beats as resoundingly as the one I found here.